The terms temperament and personality get tossed about interchangeably, when in reality they are two separate concepts.

Briefly, temperament is innate, something we are born with and can’t change, whereas personality is shaped by both internal and external factors.

Ancient Greek philosophers, physicians, and physicists came up with the concept of temperament. Temperament means “mixture.” Specifically, temperament is a mixture of the four elements (air, earth, fire, water), the four qualities (hot, cold, wet, dry), and the four humors (blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm). Physicians worked to treat imbalances in the temperament.

Plato (fifth century BCE) was the first to call earth, air, fire, and water “elements” and said that diseases resulted from deficiencies or excesses in the elements.

Hippocrates (born 460 BCE) devised the system of the humors by applying the four elements and four qualities to the human body. The macrocosm (world) was correlated to the microcosm (body). As above, so below.

Aristotle (born 384 BCE) and Stoicism (began around 300 BCE) described the “active” qualities as hot and cold.

Galens (born 131 CE) was attending physician to Marcus Aurelius and was a follower of Aristotle and Hippocrates. He embraced the humor theory of Hippocrates and the element/quality theories of both Hippocrates and Aristotle, and also correlates the four seasons to the humors. His was the first holistic theory of health because it showed a connection between personality, mind and body.

By the time of Marsilio Ficino in the 15th century, the four humors of choleric, melancholic, sanguine and phlegmatic were associated with psychological characteristics and not just physical ones.

The four humors are defined as:

Choleric – Decisive, independent, goal-oriented.

Melancholic – Low energy, deep thinkers, analytical.

Phlegmatic – Opposite of choleric. Passive, easy-going, timid, empathetic.

Sanguine – Buoyant, hopeful, confident, cheerful, robust.

All told, the temperament theory was dominant for around 1700 years.

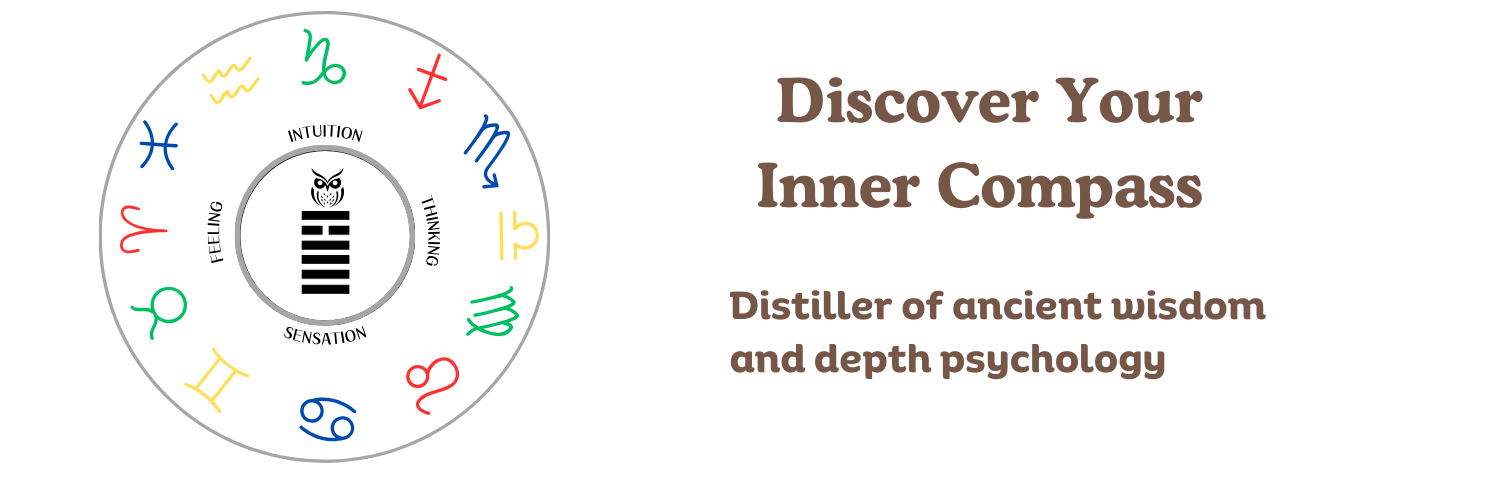

Carl Jung, in his book Psychological Types, published in 1921, came up with the four cognitive functions of thinking, feeling, sensation and intuition. He acknowledged a debt to the ancient temperament theory as a foundation from which his new typology emerged. However, Jung was critical of the temperaments:

The four temperaments are obviously differentiations in terms of affectivity, that is, they are correlated with manifest affective reactions. But this is a superficial classification from the psychological point of view; it judges only by appearance.

Psychological Types by CG Jung, paragraph 547

Jung said that a person who looks phlegmatic might actually be choleric on the inside and said that there needed to be a more objective system:

We have, therefore, to find criteria which can be accepted as binding not only by the judging subject but also by the judged object.

Psychological Types by CG Jung, paragraph 888

Jungian analyst Liz Greene, and others, have correlated his four functions to the four elements:

Earth = sensation

Air = thinking

Water = feeling

Fire = intuition

Dorian Greenbaum describes a theory that applies the four functions to the four humors. This associates the two “active” qualities of hot and dry with extroversion and introversion respectively, and also adds “wet” and “dry:”

Extraverted (hot) thinking or extraverted sensation (dry) = choleric

Extraverted (hot) feeling or extraverted intuition (wet) = sanguine

Introverted (cold) thinking or introverted sensation (dry) = melancholic

Introverted (cold) feeling or introverted intuition (wet) = phlegmatic

Combining the ancient concept of temperament with Jung’s typology is a way to enrich your understanding of your personality. Astrology is a way to find your elemental makeup, and also gives insights into personality beyond regular personality typology, which I will blog about in future posts.

Sources:

Relating by Liz Greene

Temperament: Astrology’s Forgotten Key by Dorian Gieseler Greenbaum